Washington Irving Stories: How Legend Becomes Truth

There are stories, and then there are the stories behind them. A tale well-told lingers long after the last word is read, but a tale wrapped in uncertainty and deception—now, that is a story that lives on. Washington Irving knew this well. He did not simply write “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”; he conjured them into existence, cloaking them in the guise of lost manuscripts and half-remembered folklore, so that even now, centuries later, we wonder: where does the truth end, and where does the legend begin?

I first encountered these stories in my youth, though, at the time, I did not fully grasp the depth of their spell. The specter of the Headless Horseman haunted my dreams, a ghastly rider wreathed in mist and malice. And yet, as I revisit Irving’s words now, I see fear and the craft of the deft hand that wove together history and myth until the two became indistinguishable.

Irving, ever the trickster, played with the very idea of storytelling itself. His narrator, the so-called historian Diedrich Knickerbocker, presents these tales as “discovered” manuscripts, a wink and a nod to the reader that what follows may—or may not—be true. And therein lies the magic.

A Sleep That Stole a Generation

“Rip Van Winkle” begins, as all the best stories do, with an air of mystery. The epigraph, attributed to one “Cartwright” (who may be as real as the elves Rip meets in the mountains), solemnly asserts the importance of truth. But before the ink is dry, Irving undermines this with his introduction: Knickerbocker, we are told, is a man whose accounts are “rich in that legendary lore, so invaluable to true history.”

A contradiction, if ever there was one.

What follows is a tale of a man who sleeps for twenty years, missing the American Revolution and waking to a world that has moved on without him. Before he falls into enchanted slumber, Rip drinks beneath the watchful eyes of King George III’s portrait; when he wakes, that portrait bears George Washington’s face. In a single stroke, Irving represents the passage of time, the shifting tides of history, and the fate of those who refuse—or are unable—to change with it.

So, we must ask: did Rip truly sleep for two decades, or is this merely the legend of a man too idle to grasp the world’s transformation? Did he dream it all in an alcohol-induced haze? Irving, sly as ever, does not say. He leaves us wandering the very same mountains, searching for answers.

The Ghost and the Trickster

If “Rip Van Winkle” is a tale of time slipping away unnoticed, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” is a study of perception itself. The story’s epigraph, lifted from James Thomson’s “The Castle of Indolence,” sets the tone—this is a place where reality wavers, where a man may be lost to dreams and phantoms alike. Irving grounds the tale in history, telling the capture of Major André during the Revolutionary War, but history itself bends beneath the weight of the supernatural. The Horseman, a Hessian trooper said to have lost his head to a cannonball, is more than just a legend; he haunts the very air of Sleepy Hollow.

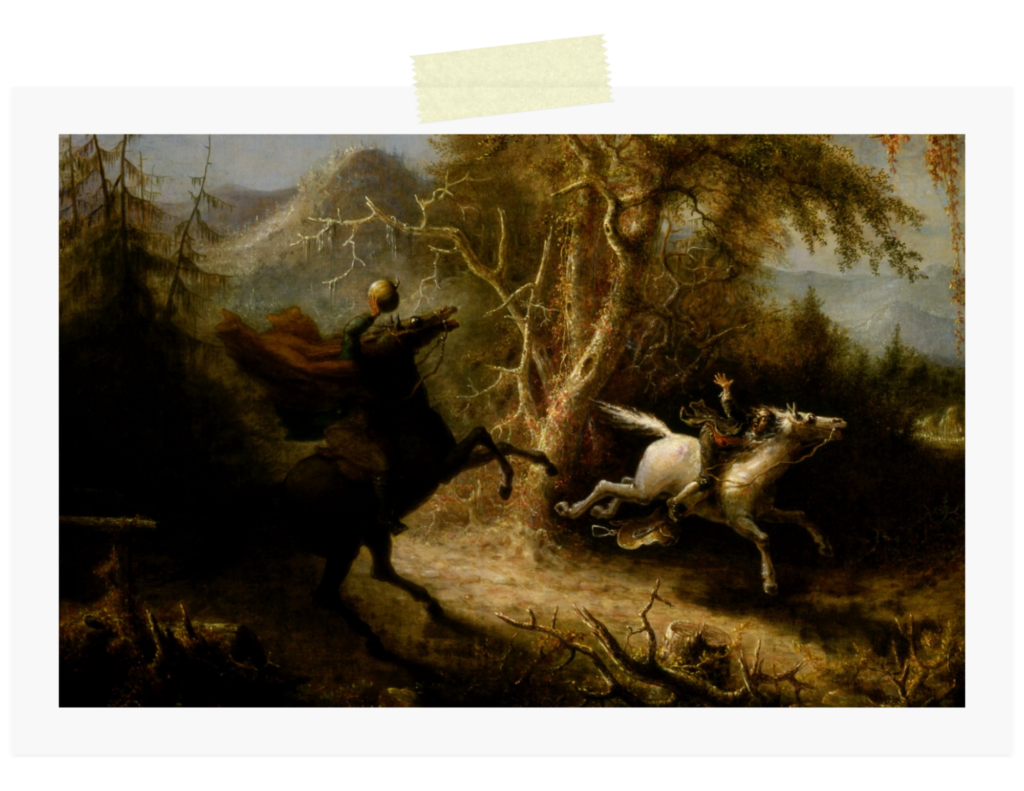

And then, of course, there is Ichabod Crane—the schoolmaster, the outsider, the man caught between myth and mockery. He is a believer, eager for tales of ghosts and spirits, a man who fears the Horseman and even invites that fear into his mind. His final ride through the dark woods is the story’s crowning moment. Hoofbeats echo. The great, silent rider looms ever closer. And then—silence. A shattered pumpkin. A disappearance.

Did Ichabod fall victim to a specter, his soul claimed by the supernatural forces he so readily embraced? Or was the Horseman nothing more than a mortal trick, the work of his rival Brom Bones? Again, Irving leaves the question unanswered. A farmer claims Ichabod still lives, that he fled Sleepy Hollow and made a new life elsewhere. But the villagers insist otherwise. He was spirited away, they say. The truth is lost, swallowed by the fog of legend.

The Power of a Story

Irving was a master illusionist. He blurred the lines of history and fantasy with each tale, making us question what we accept as truth. His use of Knickerbocker, his references to real places and historical events, and his playful contradictions remind us that once a story is told, it takes on a life of its own.

And is that not the nature of legend? A tale does not need to be true to endure. It must only be believed. The themes Irving explores—change, the passage of time, and the power of belief resonate as strongly now as they did in his day. We still tell ghost stories. We still question the past. And we still look over our shoulders when we hear hoofbeats in the dark.

So let the Horseman ride. Let Rip wander into the mountains once more. And let us, for a moment, step into the space between truth and myth, where stories live forever.

Thank you for reading.

Washington Irving Stories Washington Irving Stories Washington Irving Stories Washington Irving Stories Washington Irving Stories