“The unicorn lived in a lilac wood, and she lived all alone. She was very old, though she did not know it, and she was no longer the careless color of sea foam but rather the color of snow falling on a moonlit night. But her eyes were still clear and unwearied, and she still moved like a shadow on the sea.”

Peter S. Beagle, The Last Unicorn

There are stories that entertain, stories that thrill, and then there are those rare few that burrow into the soul, leaving marks that never fade. The Last Unicorn is such a story for me. It is more than fantasy; it is a story laden with symbolism, where every fleeting moment, every transformation, and every loss carries a weight far greater than what is seen on the surface. Even as a child, I felt it—the tragedy that lurked beneath its whimsy.

The novel, written by Peter S. Beagle and published in 1968, is one of the most haunting and poetic works of fantasy ever crafted. The animated film, created by Rankin/Bass and released in 1982, brought this dreamlike tale to life, embedding its melancholic imagery into the hearts of a generation. That was how I first met The Last Unicorn, on a VHS tape, curled up on the floor, unaware that something within me was about to shift.

I was eight years old, and even then, I knew I was different. I couldn’t name it at the time and couldn’t explain the sense of distance I felt from others, but I knew I didn’t belong in the way that others did. And so, when I landed into Beagle’s world, something stirred. It wasn’t joy, not exactly. It wasn’t sorrow, either. It was something in between—something new, something unnameable. A strange weight, an ache that didn’t quite hurt, an awareness of something vast and mysterious just beyond my grasp. The Last Unicorn was not a bright and shining fairy tale. It was dreamlike and distant, beautiful and sad, and though I didn’t fully understand what I was feeling, I knew that it was important.

Years later, I would read the book for the first time, and only then would I truly understand why it had stayed with me.

When Fantasy Feels Too Real

There was something different about this story, something that set it apart from the other unicorn tales I had seen in books and cartoons. This was a story of loneliness, of change, of loss. There was a sadness painted into every frame, every line of dialogue—a feeling of things slipping away, of something ancient and sacred being forgotten. I felt it even as a child. That slow, creeping dread.

I did not yet understand the passage of time, the fading of magic. And when the unicorn learned that she might be the last of her kind, when she wandered a world that had long since forgotten her, I could relate to what it meant to be alone. Not alone in the way of solitude, but alone in being different. The unicorn, an immortal being untouched by age, is forced into humanity—forced to experience mortality, to feel the weight of time and sorrow and longing. When I was eight, that transformation unsettled me. Now, it devastates me because I understand.

Legends, Outcasts, and Dreamers

The Unicorn / Lady Amalthea is not the naive, wide-eyed heroine of so many fairy tales. She is timeless, proud, and distant. She does not belong in the world of men, and she knows it. She sees humanity as a curse, a thing of weakness, and in becoming human, she suffers as we all do and is often mistaken for something she is not. What must it be like to be unseen for who you truly are? To know that you do not belong? At eight years old, I did not have the words, but I knew that feeling.

Schmendrick, the Magician, is no Gandalf, no wise and powerful mentor. He is a reluctant, imperfect sorcerer cursed with magic that does not always obey him. He is fumbling, uncertain, and desperate to prove himself. And yet, despite his limitations, he is the one who changes the unicorn’s fate. But not by an act of mastery—it is an accident, a magic he cannot fully control. In this world, magic does not solve problems; it is flawed and unpredictable.

Molly Grue, weary and wise, hardened by the disappointments of life, has long abandoned fairy tales and the dreams of childhood. Molly is a woman who has seen too much and felt too much to believe in the innocence she once held. The book describes how only young virgin girls possess the rare ability to tame a unicorn and ride it through the depths of the enchanted woods. When she finally sees the unicorn, she does not rejoice—she weeps, raw with fury and grief. She has waited her whole life for proof that magic still exists, and now, when it stands before her, it is too late. The years have claimed what was once hers, and in that moment, she mourns the cruel passage of time itself.

And then there’s the Red Bull, the beast that hunts the unicorns, a looming shadow, a force that speaks of time, inevitability, and loss.

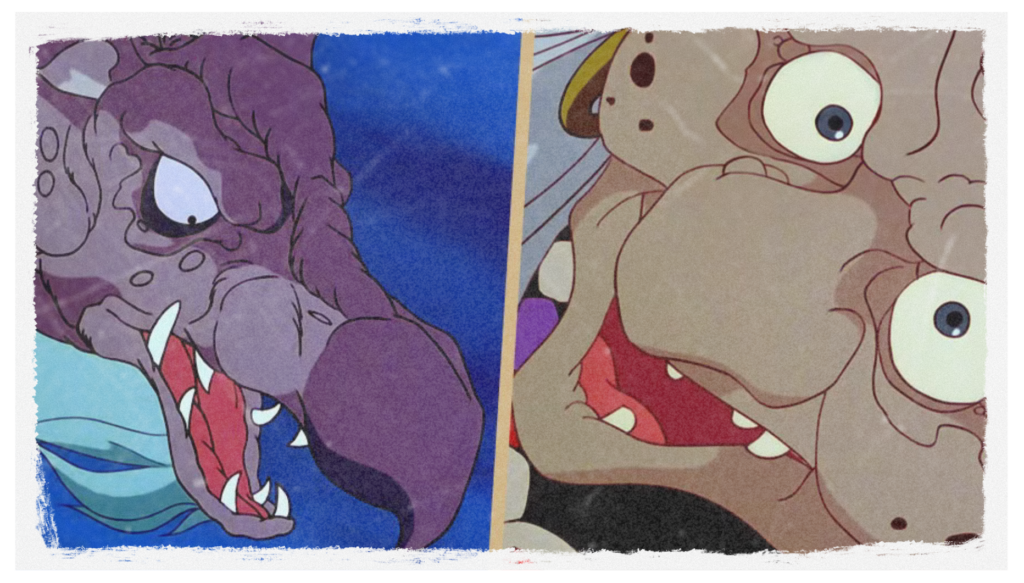

I remember the dreadful scene with Mommy Fortuna, the old witch who captures the unicorn and uses illusions to make ordinary animals look like legendary creatures. A snake becomes a dragon. An old lion becomes a manticore. Humans, she says, will believe whatever is most convenient to them.

When Celaeno, a harpy, is finally freed, she descends upon her in a blur of talons and fury. Fortuna cries out that neither the harpy nor the unicorn could have escaped without her, insisting that their freedom was only made possible by her own hand. The harpy, unchained and vengeful, tears into her as she meets the fate she had long believed herself above.

That scene terrified me. It still does.

Why The Last Unicorn Still Matters

Most tales of sorcery and legend speak of heroes, of battles fought and won, of destinies fulfilled. But The Last Unicorn is something else entirely. It is quiet, reflective, and melancholy. There is no true happy ending. Though the unicorn returns to the immortality that once defined her, she does not return untouched. She has known regret, she has felt fear, and she has glimpsed what it means to be human. She carries the weight of what she has lost and what she has felt, and that burden will never leave her.

I found this view particularly interesting:

“The last unicorn explores the doctrine of momento mori: “you will die.” And how the human characters approach and react to death and the corrupting pursuit of immortality. The unicorn represents eternity and beauty and her lesson to humans is she does not hate or love, she just IS.

The Red Bull represents humanity’s corrupting view of eternity. humans see eternity as atrophy and decay and respond ” Nothing matters so what’s the point?” This is how Haggard behaves and this is how the red bull is able to capture the unicorns. I see that demand depicted as the unicorns are herded into the sea, unable to answer him.

It is the unicorn’s brief stint as mortal that gives her the power to defeat the bull. she falls in love and discovers a mortal life full of love is preferable to immortality without it. So when the bull threatens the Prince she find the power to turn around to fight. So her answer to the Bulls question and the lesson of the story is: ‘Momento mori, yet there is LOVE’.”

u/Ok_Fun_8727, Reddit. November 24, 2023

The Lasting Spell of The Last Unicorn

The Last Unicorn shaped my understanding of storytelling. It is a novel heavy in symbolism, where every word goes deeper beyond what is written. Beagle’s use of symbolism is the unseen thread that weaves itself into every moment, something that lingers long after the last page is turned.

The beauty of symbolism is its subtlety, its ability to speak to the reader’s soul without ever declaring itself outright. A well-placed symbol can turn a simple story into a reflection of something larger. It allows a tale to exist on two planes at once, the literal and the metaphorical, giving it depth and an enduring kind of power. Even the unicorn herself is more than a creature of myth; she is innocence, memory, and the fragile remnants of magic in a world that has moved on.

In my writing, I use symbolism to layer depth beneath the surface, a technique I have Peter S. Beagle to thank for. His work taught me that the most powerful stories are not just read; they are felt, and through symbolism, we reach beyond words and into something truly unforgettable.

So, The Last Unicorn is not a sad story, not really. Because even if magic fades, even if time moves forward, some things stay with us. Some things never leave. And when I return to this story now, I understand the feelings I couldn’t name back then. Because the first fantasy you ever loved—the first one that makes you ache, that fills you with wonder, that whispers of things just beyond reach, that is the one that stays with you forever.